What is Linear Surveying

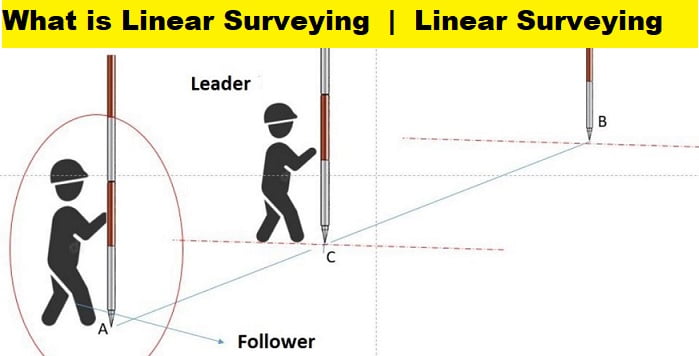

Distances between points on Earth’s surface are measured using linear surveying. Different linear surveying techniques have different advantages depending on the level of accuracy needed.

The Techniques of Linear Surveying

There are three main categories for linear surveying techniques:

- Direct measurement

- optical measurement

- Electronic methods

Direct Measurement

Distances are measured on the ground with chains, tapes, etc., in this type of surveying.

A Method of Optical Measurement

Telescopic observations are made, and distances are calculated using techniques similar to the tachometer and triangulation.

Electronic Methods

Distances are mapped out using tools that rely on the transmission, refraction, and reception of radio or light waves to create a three-dimensional image of the terrain. Subsumed under the umbrella of electronic procedures are the following types of equipment:

- Geodimeter

- Tellurometer,

- Decca Navigator, and

- lambda position fixing system.

In the case of a geodimeter, distance is determined via the transmission of modulated light waves. All three other devices measure distance with radio waves.

Why Do Surveying Errors Occur?

Surveying errors can occur from three major sources:

1. Instrumental: A surveying error can occur due to an imperfection or faulty adjustment of the instrument used to take the measurement. A tape, for example, maybe too long, or an angle measuring instrument may be out of calibration. These are referred to as instrumental errors.

2. Personal: Errors can also occur due to a lack of perfection in human vision when observing and touch when manipulating instruments. For example, an error in taking the level reading or reading an angle on the circle of a theodolite could exist. These are known as personal errors.

3. Natural: Surveying errors can also be caused by changes in natural phenomena such as temperature, humidity, gravity, wind, refraction, and magnetic declination. The results will be incorrect if they are not properly observed while taking measurements. For example, a tape maybe 20 metres long at 200 degrees Celsius, but its length will vary depending on the field temperature.

Types of Surveying Errors

Ordinary surveying errors encountered in all types of survey work can be classified as follows:

- Mistakes

- Accidental errors

- Systematic or cumulative errors

- Error compensation

Mistakes: Mistakes are errors caused by the observer’s inattention, inexperience, carelessness, poor judgement, or confusion. They have no mathematical rule (law of probability) and can be large or small, positive or negative. They cannot be quantified. They can, however, be detected by repeating the entire operation. If a mistake goes undetected, it has a serious impact on the result. As a result, every value recorded in the field must be validated by some independent field observation. The following are some examples of errors:

- Erroneous recording, such as writing 69 instead of 96

- Adding up 8 for 3

- Forgetting about chain length once

- Making errors when using a calculator

Accidental Errors: Surveying errors can occur due to unavoidable circumstances such as changes in atmospheric conditions that are completely beyond the observer’s control. This category includes surveying errors caused by flaws in measuring instruments and even poor eyesight. They could be positive or negative, and their sign could change. They are unaccounted for.

Systematic or Cumulative Errors: A systematic or cumulative error will always be the same size and sign under the same conditions. A systematic error always adheres to some definite mathematical or physical law, and correction can be determined and implemented. Such errors have a consistent character and are classified as positive or negative depending on whether they have a large or small impact on the outcome. As a result, their impact is cumulative. For example, if a tape is P cm short and is stretched N times, the total error in length measurement is P’N cm.

Systematic errors can occur due to variations in temperature, humidity, pressure, current velocity, curvature, refraction, and so on, and (ii) faulty setting or improper levelling of any instrument and an individual’s vision. Examples include the following:

- A line’s alignment is incorrect.

- An instrument is not properly levelled.

- An instrument is not properly adjusted.

Systematic errors are extremely dangerous if they go undetected. As a result, (1) all surveying equipment must be designed and used in such a way that systematic errors are automatically eliminated whenever possible, and (2) all systematic errors that cannot be surely eliminated by this means must be evaluated and their relationship to the conditions that cause them determined.

Compensating Errors: This type of surveying error can occur in both directions, i.e. the error can be positive or negative at times, compensating for each other. They tend to go in one direction and then the other, i.e. they are equally likely to produce a large or small apparent result. Some examples are as follows:

The difference in chain and tape measurements when both are used at the same time

They obey the laws of chance and must thus be handled according to the mathematical laws of probability.